Back to the calendar rules page

Why Do the Rules for the Chinese Calendar Work?

First draft: October, 2018 Last major update: April, 2019

Remember that the goal for a luni-solar calendar is to take into account both the cycle of seasons and cycle of the moon phases. It should be obvious that Rule 3 is designed to accommodate the lunar cycle. By fixing the first day of a month to the day of the new moon, days in a Chinese month are closely related to the moon phases. For example, a full month occurs on the 16th day of a month, give or take one day. Rules 4 and 5 are designed to accommodate the cycle of seasons. Since month 11 must contain the winter solstice, it is winter time in month 11. In fact, month 11 is sometimes referred to as the winter month (冬月). However, winter solstice is not fixed with respect to the lunation cycle. It can occur on the day of a new moon in one year and on the day before a new moon in another year. This means, according to Rule 3, that winter solstice can be the first day of month 11 or the last day of month 11. This is a much larger variation compared to the Gregorian calendar in which winter solstice is on Dec. 22 give or take one day every year.

Before the calendar reform in 1645, each regular month in the Chinese calendar contained a major solar term (see the discussion near the bottom of the solar terms page). For example, month 11 must contain Z11, month 12 must contain Z12, month 1 must contain Z1 and so on. After the calendar reform, this is still true most of the time but can fail on rare occasions. However, even on those rare occasions the major terms miss the associated months only by one day. Hence we can say that the 12 major solar terms are (almost always) contained in the associated 12 regular months. They can vary up to about 30 days in the calendar from years to years. This is again a larger variation compared to the Gregorian calendar in which each of the 24 solar terms is fixed to within three days from years to years. This is the price the Chinese calendar pays in order to accommodate both the lunar cycle and cycle of seasons.

It was known in China around 600 BCE that the period of 235 (= 12×19 + 7) synodic months is close to the period of 19 tropical years. This was known as the Metonic cycle in ancient Greece. In the past, the Chinese used this 19-year cycle to insert leap months in the calendar. Perhaps this is why some articles still say that 7 leap months are inserted to the Chinese calendar every 19 years today. They then explain how a leap month is to be inserted in the Chinese calendar: the rule is to designate the month that does not contain a major solar term a leap month. This is known as the no zhōngqì rule. People reading the articles may wonder why this rule guarantees 7 leap months being inserted in the calendar every 19 years. The answer is that it doesn't! For one thing, not every month without a major solar term is a leap month. It can be a fake leap month although it is very rare (see the discussion near the bottom of the example page). For another, the 19-year cycle is only an approximation. The period of 19 tropical years is about two hours shorter than the period of 235 synodic months. A calendar based on the 19-year cycle, such as the Jewish calendar, will have the year falling behind the mean tropical year by about one day in 228 years. This is, however, not the case for the Chinese calendar. The 19-year cycle was abandoned in China since the 6th century.

Before 7th century, Chinese used the píngshuò rule and pínqì rule to calculate lunar conjunctions and solar terms, which assumed that the motions of the Sun and Moon in the sky were uniform. The time interval between two successive lunar conjunctions and the time interval between two successive major solar terms were constants and were equal to the lunar and solar cycles used by the astronomical system. Before the 5th century, the lunar and solar cycles were chosen so that the ratio of the two cycles was 235:19. Since 19 solar years contained 19×12=228 major solar terms and 235=228+7, there were exactly 7 months in 19 years without a major solar term. As a result, the no zhōngqì rule guaranteed exactly 7 leap months appearing in 19 years.

It was later realized that the 235:19 ratio for the solar to lunar cycle was not very accurate. It was no longer enforced since the 5th century. For example, the Dàmíng astronomical system (大明曆) developed by Zǔ Chōngzhī (祖沖之) in 462 inserted 144 leap months in 391 years. The way to do it was to choose the ratio of solar cycle to lunar cycle to be 4836:391. Since 4836 = 391×12 + 144, the no zhōngqì rule resulted in inserting 144 leap months in 391 years. This was called the pòzhāng method (破章法), literally meaning a method that breaks the 19-year cycle. The first calendar that broke the 19-year cycle was based on the Xuánshǐ system (玄始曆), which inserted 221 leap months in 600 years. It was adopted by the Northern Liang dynasty from 412 to 439 and Northern Wei dynasty from 452 to 522 in northern China.

Since the 7th century, the píngshuò rule was abandoned in favor of the díngshuò rule (which takes into account the non-uniform motion of the Sun and Moon) to calculate the conjunctions. The time interval between two successive conjunctions was no longer constant. After 1644, the pínqì rule was abandoned in favor of the dínqì rule to calculate the solar terms, and the no zhōngqì rule was modified to the current Rule 5. Now even the time interval between two successive major solar terms is no longer constant. Hence, the 19-year cycle is long gone.

Even though the 19-year cycle is not used in arranging leap months in the Chinese calendar, the cycle is still apparent. The following table shows the leap months from N1930 to N2498 arranged in 30 rows and 7 columns. Each row represents an approximate 19-year cycle. The notation NY: m means that there is a leap month after month m in the Chinese year NY.

| Cycle | Year: leap | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N1930: 6 | N1933: 5 | N1936: 3 | N1938: 7 | N1941: 6 | N1944: 4 | N1947: 2 |

| 2 | N1949: 7 | N1952: 5 | N1955: 3 | N1957: 8 | N1960: 6 | N1963: 4 | N1966: 3 |

| 3 | N1968: 7 | N1971: 5 | N1974: 4 | N1976: 8 | N1979: 6 | N1982: 4 | N1984: 10 |

| 4 | N1987: 6 | N1990: 5 | N1993: 3 | N1995: 8 | N1998: 5 | N2001: 4 | N2004: 2 |

| 5 | N2006: 7 | N2009: 5 | N2012: 4 | N2014: 9 | N2017: 6 | N2020: 4 | N2023: 2 |

| 6 | N2025: 6 | N2028: 5 | N2031: 3 | N2033: 11 | N2036: 6 | N2039: 5 | N2042: 2 |

| 7 | N2044: 7 | N2047: 5 | N2050: 3 | N2052: 8 | N2055: 6 | N2058: 4 | N2061: 3 |

| 8 | N2063: 7 | N2066: 5 | N2069: 4 | N2071: 8 | N2074: 6 | N2077: 4 | N2080: 3 |

| 9 | N2082: 7 | N2085: 5 | N2088: 4 | N2090: 8 | N2093: 6 | N2096: 4 | N2099: 2 |

| 10 | N2101: 7 | N2104: 5 | N2107: 4 | N2109: 9 | N2112: 6 | N2115: 4 | N2118: 3 |

| 11 | N2120: 7 | N2123: 5 | N2126: 4 | N2128: 11 | N2131: 6 | N2134: 5 | N2137: 2 |

| 12 | N2139: 7 | N2142: 5 | N2145: 4 | N2147: 11 | N2150: 6 | N2153: 5 | N2156: 3 |

| 13 | N2158: 7 | N2161: 6 | N2164: 4 | N2166: 10 | N2169: 6 | N2172: 5 | N2175: 3 |

| 14 | N2177: 7 | N2180: 6 | N2183: 4 | N2186: 2 | N2188: 6 | N2191: 5 | N2194: 3 |

| 15 | N2196: 7 | N2199: 6 | N2202: 4 | N2204: 9 | N2207: 6 | N2210: 4 | N2213: 3 |

| 16 | N2215: 7 | N2218: 5 | N2221: 4 | N2223: 9 | N2226: 7 | N2229: 5 | N2232: 3 |

| 17 | N2234: 8 | N2237: 5 | N2240: 4 | N2242: 11 | N2245: 6 | N2248: 5 | N2251: 3 |

| 18 | N2253: 7 | N2256: 6 | N2259: 5 | N2262: 1 | N2264: 7 | N2267: 5 | N2270: 3 |

| 19 | N2272: 8 | N2275: 6 | N2278: 4 | N2281: 2 | N2283: 6 | N2286: 5 | N2289: 3 |

| 20 | N2291: 7 | N2294: 6 | N2297: 4 | N2300: 2 | N2302: 6 | N2305: 5 | N2308: 3 |

| 21 | N2310: 7 | N2313: 6 | N2316: 4 | N2318: 10 | N2321: 7 | N2324: 5 | N2327: 3 |

| 22 | N2329: 8 | N2332: 6 | N2335: 4 | N2338: 3 | N2340: 7 | N2343: 5 | N2346: 4 |

| 23 | N2348: 8 | N2351: 6 | N2354: 5 | N2357: 1 | N2359: 7 | N2362: 5 | N2365: 4 |

| 24 | N2367: 8 | N2370: 6 | N2373: 5 | N2376: 2 | N2378: 7 | N2381: 5 | N2384: 4 |

| 25 | N2386: 10 | N2389: 6 | N2392: 4 | N2395: 2 | N2397: 6 | N2400: 5 | N2403: 3 |

| 26 | N2405: 8 | N2408: 6 | N2411: 5 | N2414: 2 | N2416: 7 | N2419: 5 | N2422: 3 |

| 27 | N2424: 8 | N2427: 6 | N2430: 4 | N2433: 3 | N2435: 7 | N2438: 5 | N2441: 4 |

| 28 | N2443: 8 | N2446: 7 | N2449: 5 | N2452: 3 | N2454: 8 | N2457: 5 | N2460: 4 |

| 29 | N2462: 8 | N2465: 6 | N2468: 5 | N2471: 3 | N2473: 7 | N2476: 5 | N2479: 4 |

| 30 | N2481: 10 | N2484: 6 | N2487: 5 | N2490: 3 | N2492: 7 | N2495: 5 | N2498: 4 |

The table shows that the 19-year cycle is quite accurate but clearly not exact. The years in each column are separated by 19 years most of the time. The pink cells indicate that the leap months occur in the "wrong" years. For example, the last column in cycle 3 was supposed to be 19 years after N1966, but the leap month occurred a few months earlier. In each column, the leap months mostly occur after the same month, give or take one month. The yellow cells indicate that the leap months occur after the "wrong" months. For example, in cycle 6 the leap month in N2033 is supposed to occur after month 8, give or take one month, but it will occur after month 11. It is also interesting to see that in column 4 the leap months usually occur after month 8 (±1) before cycle 17, but it will change to after month 2 (±1) after cycle 17. These "anomalies" indicate that the 19-year cycle is a good approximation in the Chinese calendar but not an exact rule.

We see from the table that N2262 will be the first year after 1930 that a leap month will occur after month 1. It is actually the first time a leap month will occur after month 1 since the calendar reform in 1645.

Finally, it should be noted that it is currently impossible to calculate the times (in UTC+8) of lunar conjunctions and 24 solar terms to high precision several hundred years from now. This is due to the irregularity of Earth's rotation, which causes difficulty in predicting the number of leap seconds that will be added to UTC several hundred years from now. The times for the events after 2200 have an estimated uncertainty of a few minutes. If a lunar conjunction (or major solar term) occurs within a few minutes from midnight, the first day of the associated month (or the date of the solar term) may be off by one day. Most of the time the one-day difference will not affect the leap months, but sometimes it will. As a result, one or several of the data shown in the table might turn out to be incorrect. However, the overall pattern of the leap months will remain unchanged.

What are the average length of a month and average length of a year in the Chinese calendar? You might think that they are not easy to calculate because of the complicated rules. However, it is in fact quite easy to guess the approximate values. The average length of a year should be close to the tropical year 365.242 days and the average length of a month should be close to the synodic month 29.5306 days. We can argue by contradiction. If the average length of a month deviates significantly from the synodic month, there will be a secular drift in the time of the new moon from months to months in the Chinese calendar. It will eventually drift away from the first day of a month, but this is impossible because of Rule 3. So we conclude that the average length of a month should be close to the synodic month. A similar argument works for the average of a year. If the average length of a year is significantly different from the tropical year, there will be a secular drift of the winter solstice in the calendar from years to years and eventually the winter solstice will drift away from month 11, which contradicts Rule 4. These arguments only establish approximate values because of the subtle issue of taking averages and the fact that both the synodic month and tropical year are slowly changing with time.

Here is a better argument. Let FY+k (k is an integer) be the Julian date number at UTC noon on the New Year day of NY+k (so FY+k is an integer). Let WY+k be the Julian date number of the time of winter solstice in Gregorian year Y+k (WY+k is in general not an integer). Let ΔFY+k = FY+k - WY+k-1 be the number of days between the winter solstice in year Y+k-1 and the New Year day of NY+k at UT noon. Then the number of days in a Chinese year averaged over the years from NY to NY+n is

Y = (FY+n+1 - FY) / n = (WY+n - WY-1) / n + (ΔFY+n+1 - ΔFY) / n

The term (WY+n - WY-1) / n is the number of days between two successive winter solstices averaged over n years, which is close to a tropical year. Since the New Year day is either the second or third new moon after the winter solstice, |ΔFY+n+1 - ΔFY| < U for some constant U. We know the New Year day fluctuates between Jan. 20 and Feb. 20 each year, and the winter solstice is usually between Dec. 21 and Dec. 23. So U is probably about 30 days. The exact value of U is not important. The important thing is that U is a finite number. So as n increases, the term |ΔFY+n+1 - ΔFY| / n drops to 0 and the number of days in a Chinese year averaged over n years approaches the period between two successive winter solstices averaged over n years, which is close to a tropical year. Similar analysis can be used to argue that the average number of days in a Chinese month is close to a synodic month.

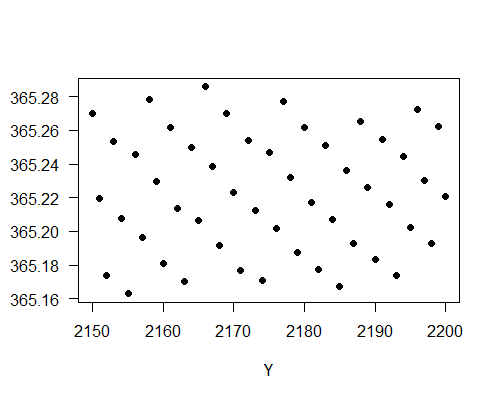

How are the guesses above compared to the actual data? Let's calculate the averages over the years from N1929 to N2200. As mentioned above, Rule 1 was imposed after 1928. That is why I start the year in N1929 to ensure consistent rules over these years. In the 272 years from N1929 to N2200, my calculation shows that there are 99340 days. Hence the average length of a year over this period is 99340/272 = 365.22 days, which differs from the tropical year by about half an hour. However, the length of a year ranges from 353 days to 385 days with a standard deviation of 14.31 days. This means that the average changes slightly depending on how many years are averaged over. For example, the average between the 271 years from N1929 to N2199 is 365.262 days; the average over the 270 years from N1929 to N2198 is 365.1926 days. We are mainly picking up the variation from the term (ΔF1930+n - ΔF1929) / n as we change n. The variation will decrease to zero as we increase the number of years. The following plot shows the length of a Chinese year averaged from N1929 to NY for Y from 2150 to 2200.

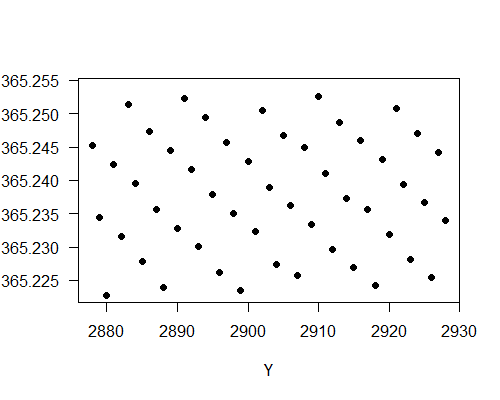

It is seen that the averages vary from 365.16 days to 365.28 days for these 50 years. This tells us the uncertainty of taking averages over about 270 years. To obtain a tighter bound on the average, we need to average over more years. The following plot shows the length of a Chinese year averaged from N1929 to NY for Y from 2878 to 2928. The average is taken over up to 1000 years.

We see that the averages over about 1000 years have values between 365.224 days to 365.255 days. The variation is about 4 times smaller. This is expected since the variation should scale with 1/n, where n is the number of years averaged over. As expected, the averages are all close to the tropical year 365.242 days.

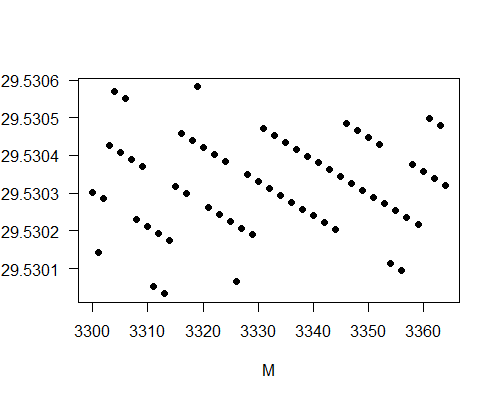

Let's now look at the average length of a Chinese month. There are 3364 months (including leap months) from N1929 to N2200 and the total number of days is 99340 days. Hence the average length of a month over these 3364 months is 99340/3364 = 29.5303 days. To see the variations of the averages, I plot the following graph showing the averages from month 1 to the month M with M from 3300 to 3364, where the month number M is counted from N1929 with leap months included.

We see that the averages show much less variations compared to the averages of a year. It is because the number of days in a month has less variation (29 days or 30 days) and we are taking averages over several thousand numbers instead of several hundred numbers. The averages vary between 29.5300 days to 29.5306 days. These are quite close to the synodic month 29.530589 days.